“The only thing worse than an employee who quits and leaves is an employee who quits and stays.” This old saying provides a good preface to the entire debate on tenure, loyalty and everything in between.

In this post, I examine the background and trends of employee tenure over the century and argue, that while commonly viewed as an indicator for loyalty and performance, tenure can easily become a restraint to the organization.

While tenure nowadays is considered a common metric in the workplace, it wasn’t always the case. Concern with this issue only arose when working for an employer (rather than self-employment) became the norm in the late 19th century.

Post war employment patterns

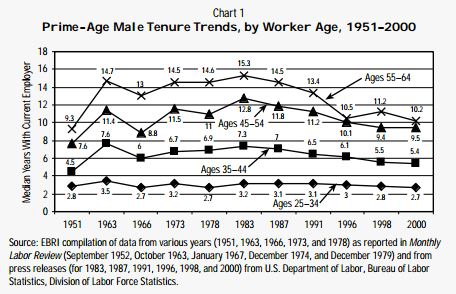

Following the second world war in the 20th century, employee attachment or tenure tended to increase across all age groups in the US. As seen in chart 1 from the the Employee Benefit Research Institute analysis, employee tenure for working-age male rose steadily from 1951, peaking at 1983. While differences appear between male and female employees as well as public and private workers, the trend tends to hold.

Driven by employee’s need for employment security, a ‘pensioner mindset’ and skills considered non-transferable between industries at that time, many spent their entire careers with a single employer.

With the rise of technology, the white collar worker, fewer unions and a more connected and competitive world, these constraints faded away and employees made more frequent moves between companies, industries and competencies. The beginning of this change is evident from the chart as we notice a decline from the 1983 peak. A decline that has accelerated with the turn of the century. It is also highlighted by Henry S. Farber, an economist at the Princeton University, in his work on Employment Insecurity: The Decline in Worker-Firm Attachment in the United States.

This phenomenon continued to the point that we now expect Millennials (born between 1977-1997) to have an average tenure of less than 3 years, according to the Future Workplace “Multiple Generations @ Work” survey of 1,189 employees and 150 managers.

This means that they would have 15-20 jobs over the course of their working lives, leading many to ask the question..

Have we become less loyal?

To that I add: Is tenure a depiction of loyalty?

If loyalty is derived from making positive impact on the organization, then does a 10-year-tenured employee add more value than a one-year-tenured new joiner? While these situations should be looked into case by case, there are some familiar corporate occurrences that can shed some light on the possible answers to this question.

The Long and winding climb

Climbing the corporate ladder is a strenuous journey, challenging our ethical stance as we try to maintain our preliminary motivation to make an impact. In addition, the learning curve tends to flatten out with seniority. If executives don’t push themselves to learn and stay engaged, they lose the very edge that got them there. As Kevin roberts, Chairman of Saatchi & Saatchi, eloquently said “the further up the company you are the stupidest you become, you are too far from anything that matters and everybody lies to you..”.

And besides, unless they belong to a tiny minority that have truly made it to the very top and have re-found their preliminary desire for impact, many of those in the middle find it justifiable to focus entirely on milking the cow for as long as they can.

Diminishing returns

And it is this tenured group that produces the many ugly sides of corporate behaviour. From window dressing and empire building to a bureaucratic, red taped fear culture. When reaching critical mass, it can completely cripple a company. With resentment to the chiefs for not getting all the way up, and a patronizing approach to the newbies, these expensive human roadblocks become part of the old guard, in the bad sense of it. Focusing purely on political mingling and alliances while preventing any change from happening. They pay lip service to innovation and ensure nobody really rocks the boat. That’s a big price to pay for ‘loyalty’.

Getting these ‘loyal’ executives out becomes extremely challenging due to their years of building internal networks, their acquired knowledge on how to work the system, and their available time to fortify their stand.

Tenurocracy?

So how can we safeguard our tenured employees from becoming sour? And how can we ensure we don’t miss out on exceptional employees because of either their ‘job hopping’ or their disappointment in a system that rewards tenure over merit (tenurocracy?).

A paradigm shift

This market wide approach needs to change. If today’s world demands agility, adaptability, creativity and people skills, we should be willing to at least remove these so called ‘job hoppers’ from our blacklists. A reality that has become widely acknowledged in the market as even governments are looking for a system that balances flexibility with security such as Denmark’s Flexicurity. However, while this topic is recognized, it has yet to be truly implemented in the actions and mindsets of organizations, perhaps due to inertia or the infamous ‘old guard’.

It should be noted that while there is merit in candidates having diverse experience, it is only relevant if real value, either by lessons learned, skill-sets sharpened or knowledge developed, has been demonstrated.

If their moves are for moves sake only, they should probably move on.

Where does this leave us?

Depending on which part of the organization you belong to (Recruitment, HR, etc..), when you were born (Generation X, Millennials, etc..) and which side of the fence you are (Hiring managers or Candidates) there is something for everyone.

Millennials – Don’t shy away from what today’s market offers you – experiences in multiple dimensions. From products, services and cultures to industries, regions and functions. Even lateral moves in different companies can provide you with both a depth and breadth of experience which can be extremely unique and desirable.

Generation X – As I often say: Millennials is not about age, it’s about mindset. Having a flexible mindset, keeping your ego in check (relevant for all generations), and willing to continuously learn and improve can make you relevant in any company or industry.

Recruitment firms/functions – As we’re asking our candidates to evolve to the new reality, so should we. We can’t miss out on the best candidates if we stick to old ‘loyalty’ paradigms. If the moves make sense, are thoughtful and there’s a consistent history of impact – you probably got yourself a winner.

HR functions – Should acknowledge that good people will eventually leave and that’s ok. To minimize the risk of the talent leaving too early, try to provide the right environment for them to develop professionally and personally. As the famous CFO/CEO discussion goes, with the CFO asking: “what if we invest in our people and they leave?” and the CEO responding: “what if we don’t and they stay?” A long tenured employee is not always the best. For him, her and the organization as a whole.

Summary

The loyalty of an employee has more to do with ethics and doing the right thing than with tenure. And the quality of the tenure will always supersede the length of it in terms of importance. For too long we have failed our long standing employees by letting them fall into the convenience trap, only to be left irrelevant when bad times come.

In turn, these long tenure employees have failed us, being the prime reason many people loath corporations and the many wrongdoings they entail.

So while tenure was synonymous to loyalty in the past, in today’s environment it can become an antonym. It’s up to all of us to acknowledge it, adapt accordingly and ensure that tenure increases due to good performance but doesn’t become an indicator of it.